Spine 2: Return to Zion (Part 6 of 9)

CP4 to CP5: Helios gets smothered by a blanket of bog

This post follows Part 5: Apollo’s photons of hope.

One of my biggest regrets from 2024 was missing out on the opportunity to enjoy Spine’s most iconic dish, the famous Alston lasagne.

I’d been unlucky. I’d caught the checkpoint team just as they were serving up the last of their vegan batch, and while they gave me some scrapings from the tray, it barely amounted to a mouthful. When I departed the checkpoint I felt as though I had unfinished business at Alston.

This year I stormed into that same Alston checkpoint on a high. I’d just broken my 3 hour target for descending from Greg’s Hut, and I hoped to ride that wave by tucking into a generous portion of the Alston checkpoint team’s finest vegan lasagne.

Well, I hit the jackpot. The team told me they were overflowing with it, and presented me a breezeblock-sized portion. With a whole Spine 2024’s worth of lasagne to make up for, I chowed through it, followed by another serving, and another, and another, and another, until I couldn’t stuff another morsel of lasagne into my mouth. That was Alston’s delicious lasagne, well and truly ticked off my Spine bucket list.

Since I was on a winning streak, what else hadn’t I experienced here at Alston? Aha, the showers! They had to be tried and tested too. My third hot shower of the race was wonderful, and I sought to polish things off nicely with a lovely relaxing sleep.

The Calm Before The Storm

I hardly cracked the dorm door by a smidgeon when the handle vibrated violently, and the ear-splitting sound of a foghorn emanated from within. What on earth? I pushed the door open and inched inside inside the darkened room, which by now had fallen silent. Goodness knows what that’d been. I used a small light to find an empty bunk, and took great care to unpack my sleeping bag as quietly as I could. Out of nowhere, the jarring sound of the foghorn erupted again. This time I could clearly comprehend the source of the offensive noise. On the opposite bunk was sleeping quite possibly the world’s loudest snorer.

It was so powerful & discordant that it physically hurt my ears. There wasn’t a chance in hell of sleeping through that. So I tried some earplugs, but faced with such violent thunder they proved to be absolutely useless. It wasn’t just the eruptions themselves, but the wildly inconsistent interval between each one that made it worse. Would the next come in 5 seconds? 10? 20? It was an ordeal in itself just trying to predict how many seconds remained before the next prodigious explosion.

As I lay there contemplating how similar this might be to sleep deprivation techniques employed in Guantanamo Bay, the knee I’d struggled with earlier began locking up. Every time I reacted instinctively with a full-body twitch that somehow always involved me whacking my broken hand, which rocketed the pain level right up to ten. Then the foghorn blared, blasting air around the room with the power of Cross Fell’s Helm Wind. I tried to sleep for hours, but not even Rip Van Winkle could have caught 40 winks in this house of horrors.

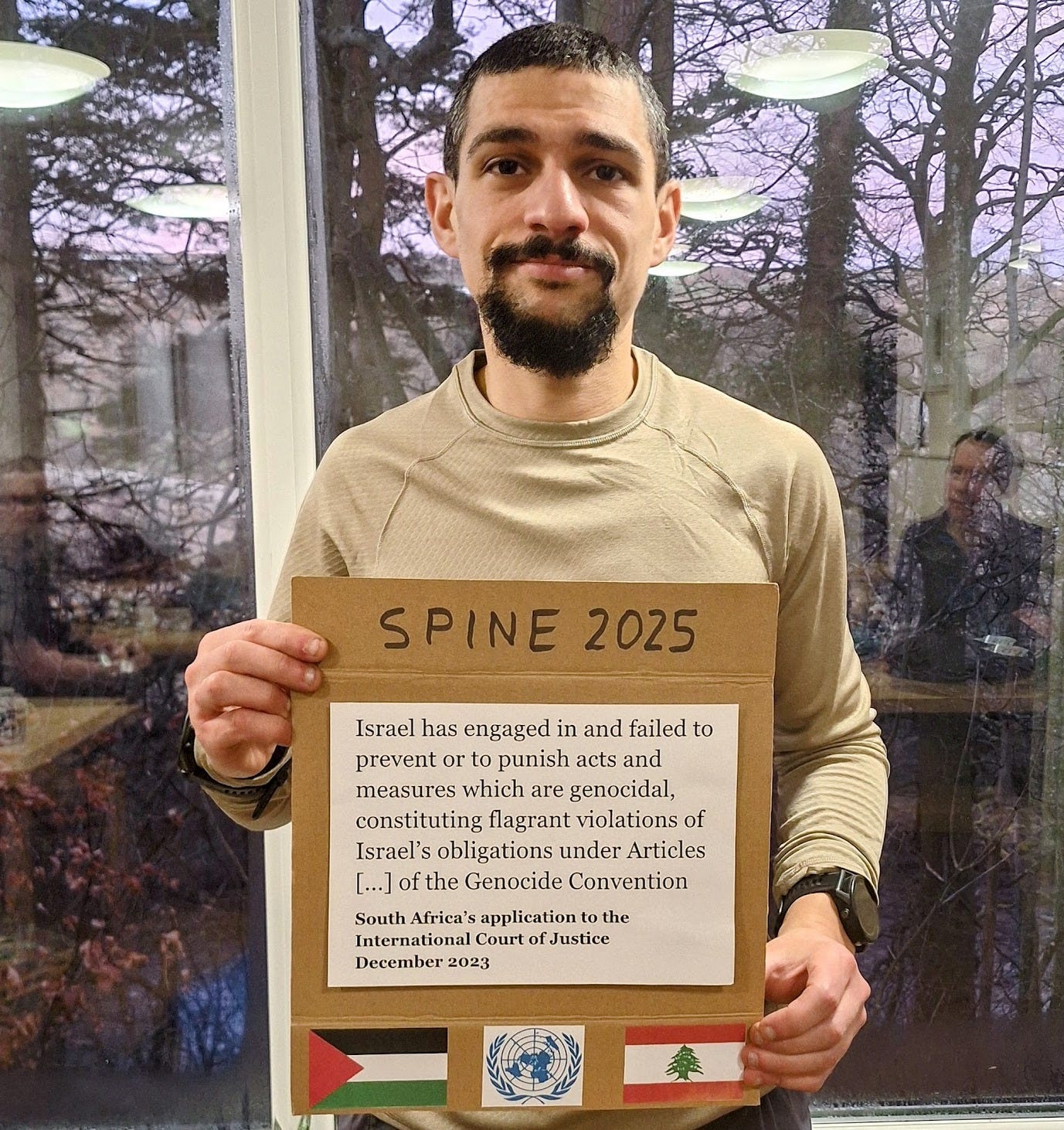

Back in the main room I felt surprisingly groggy given that I’d just been subjected to hours of auditory and physical torture. My eyelids persistently inched their way closed, so I glugged mug after mug of teas and coffees, and somehow managed to spotlight part of South Africa’s submission to the International Court of Justice:

It was appalling to think that a year after South Africa’s 99 page document with 574 references was presented to the court; not only had no effective action been taken to forestall Israel’s genocidal campaign, but throughout the US and the UK had materially enabled it.

If nothing else, that thought helped place my night of auditory torture into perspective.

Preparations for Bog Warfare

There were a handful of other runners in the room with me. Among their conversations, I was disturbed to hear occasional mentions of time cutoffs. Was I really on for a Friday or Saturday morning finish like the anonymous volunteer in Greg’s Hut had reassured me; or was I, in fact, much further behind than that? Some of the boggiest sections of the course still lay ahead of me. There was no telling how slow they might be after all the rain and snowmelt.

At that moment Leif (one of my fellow compatriots during the Pen-y-Ghent downpour) arrived. While he wore his trademark smile, there was something missing from his usually bulletproof demeanour. He wasted no time in explaining how he’d become injured over Cross Fell and would reluctantly have to bow out. It made sense as a precautionary strategy, after all he had his Arctic Spine race to think of in just a month’s time.

So, another DNF. Apart from my brother, everyone I knew was DNF’ing. What about me? I was running hours, days, who knows how long behind schedule. I might even get timed out. I was carrying injuries, fighting my tech, and still struggling with a why.

But there was also much to be positive about, I reflected. I was in better mental shape than earlier, and today’s weather forecast was much better. So much so, we had an unseasonably balmy ‘feels-like’ of positive 4°C ahead of us. Moreorless summertime on the Med!

So, to business. I started to prepare my gear. After all that rain and snowmelt, the next section could be outrageously muddy. What shoes to wear? My Mudclaws would have given me an significant advantage, but I had to consider the swelling in my feet after 300km of Spining. It made sense to prioritise comfort and breathing room, so I returned to my Mafates, whose modest 5mm lugs would have to deal with the mud as best they could.

Too Easy!

I left not long after sunrise. The sky was a bright blue, and it was calm, warm, and overall a thoroughly glorious winter morning up in north England. As someone who considers himself practically allergic to the cold, this felt like the turning of a page, and my day to shine.

The Pennine Way trail tracked parallel to the valley. Blue skies up above contrasted with the vivid greens of forested fellsides, while grassy uplands enjoyed the warm amber embrace of the morning sun.

And then the mud started. “Oh, bloomin’ heck!” “Woah; flipping hell, foot’s disappearing here…” “Wooooooah, oh my God!” The mud was both hopelessly slippery and incredibly sticky. I never quite wrapped my head around the physics of that.

Respite from the mudfest came on a 2km sprint alongside the South Tynedale Railway line, which is probably the easiest stretch of the entire Spine. I made excellent time here, in no small part due to my maintaining a solid fuelling regime.

After Slaggyford the deep, sticky mud kept coming; but in above-zero temperatures and with the sun for company, I didn’t care one iota. “What a great day! Come on!”, I exclaimed, flailing my arms while floundering through a sticky patch. “Too easy, too easy!”

‘Too easy’ is my friend Jandalf’s trademark battle cry. Today, under the glorious winter sun, I used it in jest; for the quagmire certainly was ridiculous, but in these unseasonable conditions, who cared? Keep it coming!

The route climbed up onto moorlands and traded the mud for waterlogged trods, where my squelching turned to splish-splashing. Then, at the intersection with the A689, I found a couple of plastic boxes full of goodies for hungry Spiners. Life couldn’t get much better than this!

Gazing far into the distance, I spotted a line of distinctive undulations in the landscape that had to be Hadrian’s Wall. That landmark was such a significant milestone in the race, and now it was in sight!

After 20km of solid mud-running, my legs began to tire. I’d fuelled pretty well, I reflected, just not quite enough for my effort level through the quagmire. And I had to bear in mind I didn’t have that much food remaining. So I decided to dial it back for a little while; after all, there was no particular rush.

So I checked on Steve’s progress. He was overtopping Great Dun Fell, just two minor summits from Cross Fell. Given how few dots I could see behind him I surmised he was running close to cut-offs. I sent him a message of encouragement, but I couldn’t shake the idea that something might be going horribly wrong for him. I really hoped he was OK.

Now I was travelling at a more modest pace, I was better able to immerse myself in my surroundings. It all looked so vivid. Deep navy-blues from the waterlogged trail. Maroon puddles, perhaps from iron leaching into the water? Luscious green grass. Injections of warm browns from unfamiliar vegetation. Light yellows from inexplicably parched grasses. Sheep added the odd puff of bright white. Old tree trunks balanced the scene with lines of rustic grey. Then, a roofless ruin, still standing, as defiant as it was dilapidated.

“I’m not having to worry about falling on ice, or whether I’ve got enough layers to fend off hypothermia. I’m not juggling multiple pairs of gloves and mitts over my broken hand. I can see around me. I’m able to focus on my running. I’m loving this!”

A Disobedient Digital Twin

I well recalled the little footbridge crossing over Hartley Burn, for it was nestled within a enticingly cosy depression in the landscape. Climbing out of it I spotted a chap up ahead, and conceived the idea of using OpenTracking to find his name so I could greet him when I passed. But when I did pull up abreast, I could see he wasn’t in the frame of mind for a chat. In fact, his eyes appeared closed, he was barely awake, and I found it remarkable he was still upright and moving.

A quarter of an hour later, I reopened OpenTracking to check how my sleeprunning compatriot was getting along, but OpenTracking still showed my dot in the same place it was 15 minutes ago. I kept checking periodically, and my dot steadfastly refused to move. My phone had mobile signal, so the GPS tracker ought to as well. I checked the tracker unit, and couldn’t see any lights blinking. Had it malfunctioned, I wondered? That’d be weird, I was pretty sure it wasn’t a Garmin device…

Eventually I gave race HQ a call to make them aware something was up. They reassured me they’d look into it, and asked how I was doing.

“Fantastic!” I yelled, far too loudly into the receiver, as I barrelled down a boggy hill with a beaming smile. “The sun’s out!”

It wasn’t long before my dot took an Olympic leap up OpenTracking’s map, and HQ called me back to tell me the problem had been resolved. My dot was back on the move, and nothing could stop me now.

And nothing did for a while, until I reached the little banked descent linking Haltwhistle Golf Club to the B6318. I stood with my hands on my hips, laughing out loud. This mudfest would’ve been a dream for a Tough Mudder course. “Dig in with your hee— Woa! Bloody hell!”

Mysterious Pauses

The past couple of days, I’d experienced a frustrating phenomenon. Alongside all the other baffling problems with my Garmin watches, on a few occasions I’d found my Forerunner 955’s activity had paused.

I felt fairly confident I hadn’t done it, either on purpose or by accident, though it was admittedly impossible to be certain. My 955 was buried under many sleeves and subject to activity such as the removal of mitts and gloves. I could have been hitting the pause button by accident.

This had kept me in a mild state of paranoia for days. With every vibration of the 955, I’d felt the urge to roll up my sleeves to check whether that buzz signalled the pausing of the activity. But even when I did roll up my sleeves to check, the act of rolling them back down over the watch itself risked an accidental pause. At that rate, I could have gotten myself into an infinite pause-checking loop. The situation had been driving me potty.

I was a couple of kilometres out from Walltown and the start of Hadrian’s Wall when I made a crucial breakthrough in the Mystery of the Pausing Garmin. I had both sleeves rolled all the way up my arms and I wasn’t wearing any gloves, so there was nothing anywhere near my watches. I’d been looking directly at the 955’s watchface, reading the map, when I watched it pause and drop to the resume screen. All by itself, entirely uncommanded.

Seeing it happen in front of my eyes felt such a relief. It meant I hadn’t been imagining it! I hadn’t suddenly started to hit watch buttons accidentally. The Garmin was quite simply f***ed.

Not ten minutes later, navigating alongside a golf course using my other watch, the Enduro 2, my jaw dropped to the fairway when I witnessed the Enduro do exactly the same thing.

Both of my top-end Garmin watches had, within 10 minutes of each other, paused their activities uncommanded. Borderline unbelievable, but true.

Borderline

Walltown car park marks our entry point to Hadrian’s Wall. To my complete surprise, the Walltown visitor centre was open to us, which it hadn’t been last year (at least, not at the time I’d passed it). A member of Northumberland National Park staff ushered me inside in hushed tones. A runner was sleeping by the fire, she explained. Indeed; he looked pretty snug, curled up like a cat.

I definitely could have used some food to augment my dwindling supplies; but alas, this wasn’t a food stop, and the few offerings that’d been kindly donated by locals didn’t look particularly vegan. While I would just as well have run on, I reminded myself of my promise to engage fully with the Spine experience, so I decided to stay a while for a tea and a whispered chat.

I also used the opportunity to check on Steve. He’d only just left Greg’s Hut, and he seemed to be one of the two last runners on the course. I crossed my fingers, willing that he and Heine would motivate each other to remain ahead of that looming cut-off.

In the short space of time I’d been inside, the wind had picked up and the temperature plummeted quite unpleasantly; but as I rose up onto Hadrian’s Wall itself, Helios used the last of his influence to calm the wind, while casting his waning magic rays down onto me. In his pleasant company, I felt content once more.

It looked glorious, Hadrian’s Wall, under the sunset. The drystone snaked its way far into the distance, over serene rolling undulations counterposed with harsh crags of dark rock. The warm glow over its grassy hills evoked images of summer picnics and frolics while, edging in as the light faded, cool shadows cast over forsaken rocks surrounded by untold miles of desolate bogland and dark, dense woodlands.

O’er the wall I could just spot the southern edge of Kielder Forest, England’s largest. I hoped to reach there soon.

6km along the wall’s mythic journey brought me to the car park at Cawfield. This wasn’t yet halfway along our Hadrian’s Wall segment, and already it had worn thin. The endless route choices, climbs and dips; the falling temperature, and at 340km, over 100 hours into the run, my feet were growing increasingly painful. I had to knuckle down for a long, arduous slog along the remaining 8km of the wall.

When I finally reached the turnoff, I whooped with delight! I felt certain that faster terrain lay ahead of me. Besides which, from here, I’d stop heading east toward Newcastle, and instead turn north, to Scotland. Which was excellent news, because Scotland was where the Spinebow ended.

Quest for Chunky Broth

Alas, my elation was short-lived. Mere seconds from Hadrian’s Wall, I found myself engaged in yet another battle through Gaia’s sticky, squelchy, mud-bog-quagmire-mess. I could see this was going to be the general theme all the way to Bellingham.

The strangest thing, I found, was how the climate had transitioned on a dime. It was as though turning north from Hadrian’s Wall had signalled the start of ‘North England’ proper, where the temperature was colder and the conditions harsher. My feet started crunching over frosted mud, and I paused to add whatever clothes I had left.

Following a long climb away from Greenlee Lough, I encountered a style that afforded an excellent vantage point for me to perch atop and really take in my surroundings.

The sky was pitch black, just like it had been at Tan Hill and Cross Fell. I looked far out to the horizon, and rotated 360° to build a complete picture. Across the infinite inky void, I could spot but two pinpricks of white light, two little red dots on what I presumed to be a pylon, and a hazy glow from what I suspected must be a city far, far beyond the horizon. Out here in the blanket bog, it was just Gaia and I.

That bog remained challenging, with only subtle alterations to mud, or frosted mud, or water. And in the now freezing temperatures, I was coughing that good ol’ ‘Spine cough’ again. Being almost out of food, the best I could do was break out a pair of handwarmers to help raise my spirits.

I’d been eagerly counting down the metres to the only reprieve along this stretch, an outbuilding at Horneystead Farm. A place a lonesome Spiner can be assured of a roof over their head and some hot chunky vegetable broth, no matter the time of day. And after last year, I knew what I was looking out for: a style atop a wooded fell that overlooked a gully, beyond which would lay this haven of respite.

When that style finally came, it was with a sense of deep satisfaction that I stood tall astride it, as if I were a rancher surveying my herd, beaming at the sight of that humble hospice across the ravine. It might not be much, but in the middle of England’s largest area of blanket bog, in negative whatever °C it was, Horneystead’s voluntary provision of love represented more than help. It represented hope.

There were no volunteers outside the farm to welcome me inside like last year, but that was probably because it was approaching 9pm, and besides which it had grown so cold that I’d not have wished such a role on anyone.

I found someone inside the little outbuilding though. A runner, outstretched on a chair, swaddled in blankets, sound asleep. I tried my best not to disturb him while I retrieved a mug from beside the sink and ladled in vegetable broth from the slow cooker.

After my first mug of chunky vegetable broth, Andrew stirred, bid me farewell and headed back off into the arctic bogland. I stayed for a while, just as silently as I’d been in his presence, enjoying another mug of chunky broth and reflecting on the epic journey that’d brought me to this point.

It was at CP1.5 where I’d most seriously questioned why I was back here on the Spine again. That was days ago now. So much had happened since. Everyone I knew had either dropped or was struggling, and whilst I’d developed some thoughts on my why, I still didn’t have a clear answer.

I wrapped my hands around the hot mug, leant back and cogitated.

Hardy People of Bellingham

It was on autopilot that I navigated the remainder of my way to Bellingham, through bog and over ice, through temperatures that felt just as cold as last year, though I knew they probably weren’t.

When I finally summited the last hill overlooking the town of Bellingham, I beamed triumphantly at the town’s lights. Steadying myself against the ripping wind, I bellowed like a town crier: “Hardy people of Bellingham! Surrounded by bogs, tolerating arctic temperatures - I salute you!”

It was with a sense of heavy resignation that I ran down into the Bellingham checkpoint.

The last two legs of the Spine - overtop to Byrness CP5.5, and then over the Cheviots to Kirk Yetholm - are each such serious undertakings in their own right.

And for what? There were no more Keld Tearooms or Tan Hill Inns to visit. There was no more of Alston’s lasagne to devour. Nothing new to experience from now on.

I was running hours if not days behind last year’s time. I was tired, battered, injured, freezing bloody cold, 365km in, and I still had no f***ing idea why I was here.

I should have quit days ago. But I couldn’t quit now. The sunk cost fallacy was playing out: I’d already been through too much.

Everything rested on this illusory box waiting for me at the end of the Spinebow.

The box holding all the answers.

Holding the monkey.

Holding the why.

This box had better f***ing be there.

Continue reading Part 7: