Spine 2: Return to Zion (Part 5 of 9)

CP3 to CP4: Apollo's photons of hope

This post follows Part 4: Frozen in time: Chronos’ revenge.

The fire in the hearth was beginning to die down, but even in its diminished state it maintained a mesmerising charm.

Its flames and embers coexisted in a complementary state of yin and yang. The embers foreshadowed the flames’ demise, but were themselves living on borrowed time. Time... wasn’t it time to go home? Home… wasn’t that where the hearth is?

After the double Garmin watch meltdown, I’d mentally disconnected from the race and had little to no interest in continuing. My only remaining focus was on food, and all the more since Langdon Beck was the curry checkpoint. I had to restrain myself from asking for mine very, very, very spicy!

Then I settled on a nice hot shower, and finally to sleep.

I was directed to a 4-bunk bedroom that, as luck would have it, I had entirely to myself. With no need to worry about light or noise levels, I could spread out, inflate my pillow and settle down comfortably for a proper sleep.

I clocked up 3 hours of fruitful recuperation, my first successful sleep some 70 hours into the race. Then I refuelled with some beans on toast. I couldn’t decide between tea and coffee, so I went for both.

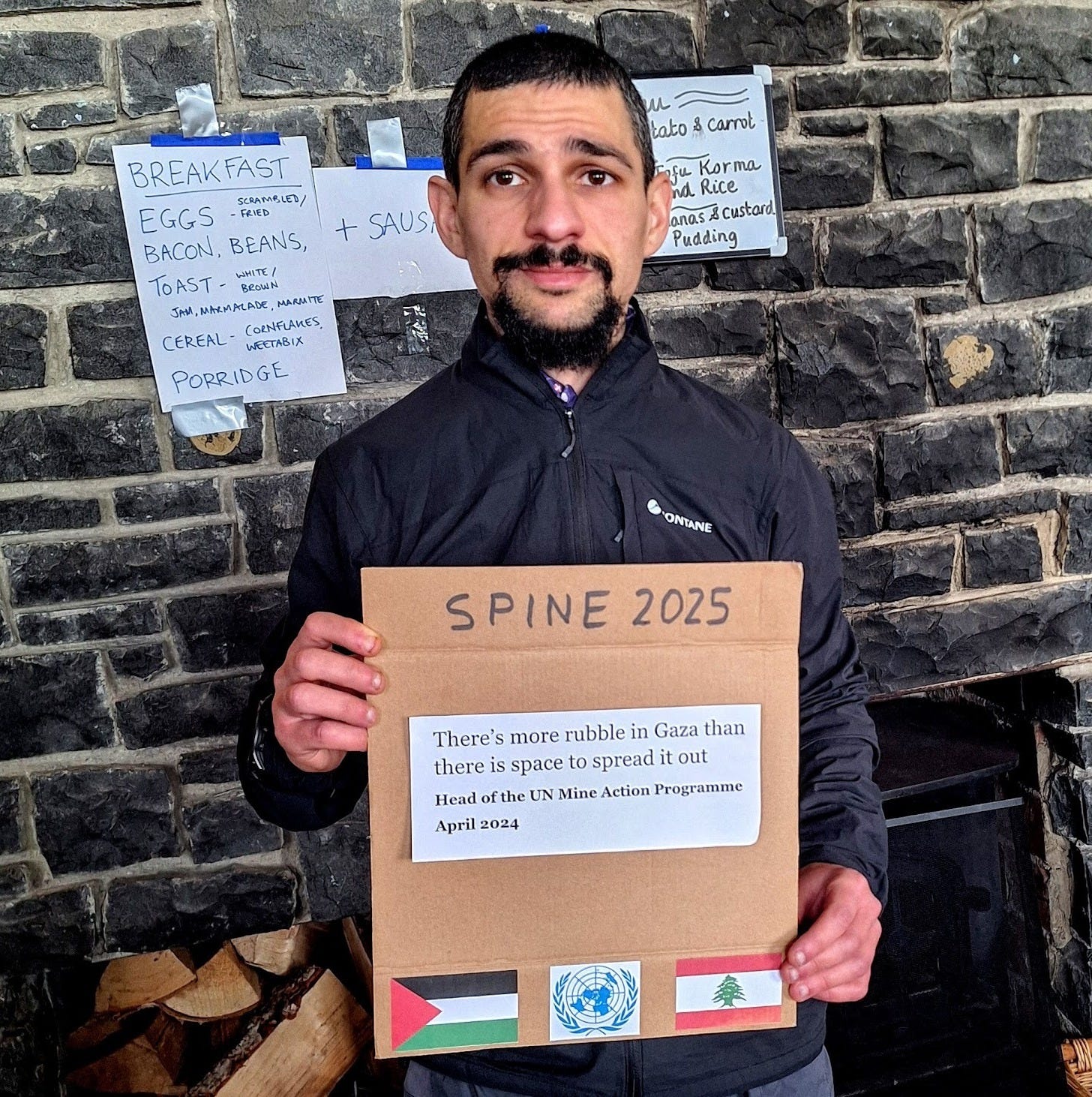

It was time for my third spotlight: a statement from Charles Birch, Chief of the United Nations’ Mine Action Programme in Palestine:

Right. It was time to decide what I was doing. Was I going home, or was I continuing?

I left the question hanging while I proceeded down my checkpoint checklist; rattling through it at pace, without giving it much thought.

I kept it hanging through kit check and departure. Then I was running again.

Much like my ‘observer’ status at the start of the race, I wasn’t committing to anything at this point. It just made sense to start running the next leg, while I made up my mind...

Finding My Way

We were diverted around Cauldron Snout for the second year running. Signage had been installed to point the way. I did vaguely recall the diversion route from last year, but for extra reassurance I fired up my Garmin eTrex handheld GPS, upon which I’d loaded the diversion routes.

It took so long to coax the antiquated brick into life, get a GPS fix and load the course, that I’d already run half the diversion by the time it started working. Then I found basic operations like zooming in so aggravatingly slow that I just threw it back in my pack. I didn’t need any more of Garmin’s provocations to throw in the towel and quit. Anyway, in the daylight, the physical signage was quite simple to follow.

The morning weather was favourable (though chilly, requiring 4 layers and a buff over my face), and the underfoot conditions much improved. There was hardly any snow remaining, other than some festive dusting on the felltops. Shafts of sunlight teased between distant clouds. It showed promise, and gave me hope that today might be a better day.

“I want to make sure I get the full experience this time; see it all, because I doubt I’ll do it a third time”, I mused.

“I’m trying to get as much out of this as I can”.

The diversion rejoined the official route to cross the dam above Cauldron Snout, after which I entered what felt like a strange place. I’d only seen this section of the course in thick snow, either in poor visibility, or darkness, or both. But today the visibility was great, conditions were good, and instead of snow there was just green, tufty grass and muddy bogs.

The lay of the land didn’t look anything like I’d imagined it from those long slogs illuminated only by a little cone of light, and so I found it difficult to reconcile what was in front of my eyes with the mental map I’d built up.

High Cap Knee

From this point, the route has no phone signal. Even the Spine’s GPS trackers can’t ping out location beacons (since they use the mobile networks). Until High Cup Nick, Birkdale Farm was our last opportunity for emergency communications, and even that was only possible thanks to the temporary satellite link and WiFi access point that the Spine team installed there. So, if I were to break a leg, all things considered, it’d be best to do it right here.

One moment my left knee was normal, and the next it wasn’t. I could hardly bend it, and was in considerable pain. I didn’t know what I’d done exactly, but it involved the kneecap and surrounding musculature. This was the same knee I’d injured 6 months ago in the Pyrenees, and had never fully managed to repair. Now, after pluckily surviving 260km of the Pennine Way, the poor thing had finally given out.

I remained in fairly good spirits, because it didn’t matter; whatever my why was, it wasn’t time-dependent. I’d just keep moving as best I could, in the form of a slow walk featuring a massive lumbering limp. In some ways this was quite similar to my shoulder episode near Middleton, I reflected. I was on pretty runnable terrain, yet I couldn’t physically run.

I kept positive by admiring the scenery, praising the weather, trying to reimagine this landscape as it was under the snow covering of yesteryear. Anything I could to distract from the pain in my knee.

As it had before, the wind picked up when I climbed away from Maize Beck onto High Cup Plain, and I began to suffer in the cold. My sloppy kit preparation hadn’t accounted for this wind chill on top of an injury. It raised the question of just how well-equipped I was for Cross Fell, which is renowned for some of the strongest winds in the country.

Rounding over the slightly boggy plain, a vista I’d been eagerly awaiting emerged in front of me, in all its majesty. Behold, High Cup Nick.

Every time I see it, it draws me in and holds my attention like a vice. It’s unrealistically dramatic, as if it were an exaggerated landscape painting. At the heart of the drama is the harmonious dissonance between the grace of the valley’s gently sweeping sides, alongside its ominous shadows and foreboding rocky outcrops.

Today, High Cup Nick was especially atmospheric. The late afternoon sun was setting dead-centre, its light heavily diffused through layers of cloud and mist that wrapped the valley like a blanket. While the howling wind pressured me onwards, I stayed firmly put, absorbing the grandeur of the scene before me.

Had I Been Framed?

Into the descent down to Dufton, I became aware of a runner approaching, though still a way behind me. I couldn’t accept them sprinting past me while I limped down like an invalid, so I gritted my teeth and insisted my knackered knee submit to something resembling a run. Within seconds, my fast hobble met its match on a slippery mudslide, and I wiped out impressively, rolling and sliding down through mud, rock and scree.

Both my leggings and my legs took a thorough beating. Even more self-conscious now I was plastered in mud and blood, I staggered on with my limping run, hoping the other runner hadn’t witnessed my You’ve Been Framed moment. I was grateful when he passed without making comment.

Funnily enough, the more I forced the knee to run, the more all its musculature loosened, and the easier it became. By the time I reached Dufton, my knee was much improved. I felt incredibly lucky that I could now continue with good speed, where I could so easily have been forced to retire.

My arrival into Dufton brought with it another opportunity to build purpose into this year’s Spine. Last time, I’d run straight past the Post Box Pantry café, my head at right-angles, lustfully gazing through its windows at the cosy interior. I thought I saw the shopkeeper smiling back, eager to welcome me inside. I’d deeply regretted not stopping there.

So, while my racing brain knew I ought to keep on going; to make the best of the setting sun, and to keep the blood flowing around my knackered knee, my why overruled all that.

Nobody Mention The Spine

I edged discreetly inside the Post Box Pantry, painfully aware it was full of diners enjoying their afternoon teas, who would likely not appreciate a Spine runner invading their space, leaving a trail of mud and blood in their wake. I tried to stay under the radar, choosing a route to the counter that allowed me to hide my legs behind other diners, tables and chairs.

Trying to appear as normal as possible under the circumstances, I ordered a vegan breakfast and tea, then made a beeline to a spare table, shoving my legs underneath as quickly as I could. That’d gone fairly well, I thought. I didn’t think the other diners had noticed me.

I spotted a TV in the corner of the room, and was surprised to see it showing the Spine’s OpenTracking map. It was focused on the descent from High Cup Nick to the Pantry. I looked around, and could see some of the diners watching it. It began to dawn on me that they’d watched me descend. They’d probably seen my name. Perhaps they’d been waiting for me to come in.

Then someone from the next table leant over to me and asked “How’s it been so far, Adrian?” And when I looked around I could see the eyes of everyone in the café staring straight at me, waiting with baited breath to hear runner 122 tell their story of Britain’s most brutal race.

It took a while to extract myself from my attentive audience in the Pantry. I only had to travel a few hundred metres up the road to reach the next stop, CP3.5 at Dufton Village Hall. There I availed myself of the opportunity to add my spare baselayer, expecting that I might suffer from exposure over Cross Fell in my relatively lightweight upper layers. And if my knee failed again; well, things could become thoroughly miserable up there. It was best to be prepared.

Blown Away

By the time I departed, light was fading and I had to add my headtorch. I thought I could remember pretty well the ascent route up Knock Fell, but its many false summits still took me by surprise.

I’d traversed Cross Fell twice before. The first time it’d been dark and foggy with very low visibility, and on the second the whole range was plastered in deep snow. Tonight, for the first time, I could see the ground as far as my headtorch could illuminate. The Pennine Way’s flagstones stretched out before me, snaking their way over the undulations of what was at present a pretty boggy and waterlogged moor.

While initially buoyed by the flagstones’ presence, my enthusiasm for them waned as I began to slip and slide. Wafer thin, hard-to-spot patches of ice seemed to be the cause. Also, the flagstones often vanished beneath 50-metre-wide pools of water.

Given all the hazards, I chose to avoid the flagstones entirely. Instead I hopped and leapt through the bog, and occasionally I misjudged it and sunk in.

I’d forgotten the strange way the Helm Wind works over this particular ridgeline of fells. You might, like me, assume the wind would be strongest over the summits. While it’s rip-roaringly wild up top, it’s actually in-between the summits in the cols where the wind blasts through at its fiercest. Tonight was no exception.

It hit me hardest in the dip between Great Dun Fell and Little Dun Fell. The Helm Wind shrieked past my ears and tore through my windproofs as if they just weren’t there. My ears and nose froze, my core temperature plummeted, and I hammered the climb as furiously as I could to generate body heat.

The summits had a totally different microclimate. Despite the wind, they felt warm in comparison, so much so that I felt quite comfy up here in my layers. The wind was still strong enough that I could tilt my body 30° into the wall of air and remain quite stationary, comfortably resting on my air blanket. In fact, I found I could do this while running too. I could close my eyes, and casually doze off, all while running and resting on my own Helm Wind airbed.

I See You

Cross Fell is the climax of the whole ridgeline. It’s the highest place in England outside of the Lake District, and one of the windiest. Despite the forces of nature working to blow one clean off the summit, I’ve always found it a place of wonderment and contemplation. And tonight, it didn’t disappoint.

As soon as I set foot on its expansive top, I felt a sense of calm spread through my body. I positioned myself behind some rocks to shield my body from the worst of the wind, took off my pack and rested on a rock. The view from here was divine. Perfect visibility afforded me a line of sight that ran for tens if not hundreds of miles, with the most distant pinpricks of light appearing indistinguishable from the stars in the sky.

That large cluster of lights to the north - could it be Carlisle? That was some 20 miles as the crow flies. To the east and west, there wasn’t so much, just odd pinpricks of light here and there. Some diffuse glows on the horizon hinted at the possibility of urban centres further beyond, but they would have been far, far away. A monumental distance across a vast expanse of terrain. Days of travelling.

Even the closest light I could see was rather far below and quite far away. I really was all alone up here. Just me, the boggy ridge, a pile of stones, and the Helm Wind for company. Up here, I was on the top of the world.

I had with me a bivvy, sleeping bag, stove and water. I thought about setting myself up here for the night. I’d have been quite comfortable. Far away from all the exigencies and trappings of modern life. From all the invasive technology platforms and their divisive algorithms. From the politics of division, hate, power and greed. From the wars and genocides, the trickeries and deceits, the megalomanias and socio-psychopathies. There was none of that up here. None at all.

My breathing had slowed to a meditative state. I was absorbing the tiny beams of light from the homes far below and the stars far above. Each beam of photons distilled something so complex into something so simple. My existence depended on all of it, be that Jupiter’s vast gravitational force bringing order to our Milky Way, to the worker at the water company making sure there’s drinking water for me to refill my bottles at the next CP.

But I’d been here a while, and it was probably time to bid Cross Fell farewell for now. I picked myself up, slung my pack over my back, gave Cross Fell one last hat-tip, and then launched into an frenzied, arms-flailing descent down to Greg’s Hut.

The Target

I was saddened not to find John Bamber in the hut on this occasion, but gladdened to find he’d left a jar of his homemade chilliewack on the table. So when I prepared one of my bland and unappetising dehydrated meals, I took great pleasure in introducing some va-va-voom to it by spooning on as much of John’s chilliewack as I felt I could morally defend. Because John’s chilliewack was bloody marvellous!

One of the volunteers struck up a conversation with me, asking how things were going, and so I offloaded what was on my mind that minute: how contented I felt that my brother had successfully completed Challenger South. She asked his time, and I reiterated what I’d been told at CP2, that it’d been within an hour of the final cutoff. “He must have been under such pressure”, I reflected.

She asked his name, and when I told her, she raised an eyebrow. “I saw him at Hawes. I’m sure I did. But he didn’t finish in 59 hours!” She explained he’d arrived around the same time as one of her friends, and that had been much earlier.

Both of us were confused now, so she double-checked my brother’s result for me on her phone. And there it was, in black and white: not 59 hours, but 54. Five whole hours earlier than I’d thought. Awesome! We both shared in the joy of that realisation, while I savoured the last dollop of spicy sauce.

Just before I left, the volunteer caught me and, with a beaming smile, she framed the remainder of the race in her unique, enheartening way. I’d be down at Alston CP in just a few hours, and then on to the finish on Friday - or early Saturday morning, at the very latest, she explained.

She said it all so assuredly that I couldn’t help but believe her, even though her estimates ran quite counter to my own. I’d made such slow progress and was so far behind where I ought to be that I’d entertained the thought that I might not finish before Sunday, or even before the final cutoff… But who was I to argue with such certitude?

So when I left Greg’s Hut and hit the long, runnable track down to Garrigill, I had her conviction playing in my mind. I ate more food, dropped a mitt and backtracked a bloody long way to find it, and all the while I couldn’t shake the feeling that perhaps she was right.

I considered my context. My knee was OK right this moment. Alston was about 18km away. 3 hours was the target she’d set. That meant I’d need to exceed 6km/hour.

6km/hour mightn’t sound like much. After all, that’s just 10 minute kilometres, which is basically a decent walking pace. But the Pennine Way at the height of winter is not a 10 minute/km walking route. Consider that the winner of the Spine, an elite runner and seasoned veteran of the Pennine Way, would travel slower than 11 min/kms over the duration of the race.

That said, I still had 7km of descent ahead of me down to Garrigill, and I remembered it being a decent, runnable track. I stood a chance at least.

So I pushed hard on the descent, flying over all those jutting stones that carved into my sore feet, guided by the lure of Garrigill’s lights below.

I recalled that Spiners talk about Annie in Garrigill, someone who often appears to offer food and water. However I hadn’t seen her last year, and so wondered whether she might be helping out today.

It just so happened that I was overtaking another runner (the first I’d seen in hours) on the main street through Garrigill at the very moment Annie came out of her house and waved to us both, calling out offers of tea and supplies. I was surprised the runner I was passing didn’t respond, but when I looked at his face I saw an expression so tired I doubted he’d either seen or heard her. So it was for both of us that I waved back, smiled, and thanked her for her generosity.

It wasn’t until I’d passed that I realised I’d broken my own purposeful rule, to experience everything to the fullest. Should I have availed myself of a cup of tea and a chat? But I considered I was temporarily engaged in a new purpose, to reach Alston before 1:20am, within my 3 hour target. I had to keep up the pace, and so felt I could forgive my transgression.

Last year the Pennine Way had an official diversion around the South Tyne River path, cutting an astonishingly awkward route through outrageously muddy quagmires that’d make our southern cross country races look like road runs. Not to mention the awkward styles every 50 metres, squeezes alongside barbed wire fences, and other such nonsense.

I was nonplussed to find the diversion still in place. I thought I’d remembered how dire it was from last year, but this year seemed so much worse, probably because last year’s icing had mitigated the worst of the abominable mud. It wasn’t what I fancied dealing with after 300kms of Pennine Way carnage.

But I was acutely aware that time was ticking and my 3 hour target was fast approaching, so I gave that last awkward stretch to Alston everything I could. I banned myself from checking the time, lest its proximity to my target of 01:20 caused me to lose hope and back off the pace.

The Moment of Truth

It was with a duality of celebration and trepidation that I spotted the trail’s turning into the YHA up ahead. I couldn’t have exceeded 3 hours, I just couldn’t. There deserved to be a good news story here.

Only when standing in the entrance to Alston YHA did I finally allow myself to check the time. I grimaced, expecting the worst. Nothing else had gone right, why should this have?

I did a double-take when I saw the time, and I paused to double-check my calculations, but they were correct. I’d taken a couple of minutes under 3 hours. I’d made it! Something I’d done had worked!

And it’d all been thanks to an anonymous volunteer back in Greg’s Hut.

I cast my mind back to Cross Fell, where photons visited me from near and far. Even in that most remote of locations, I’d felt the strongest sense of unity and community.

As the volunteers at Alston cheerily welcomed me in, despite my muddy, smelly and practically punch-drunk demeanour, I smiled in appreciation of how immensely fortunate I was to be partaking in this crazy event once more.

How fortunate I was to be back in Zion.

Where the stars shine brightly, and our community shines brightest.

Continue reading Part 6: