Spine 2: Return to Zion (Part 3 of 9)

CP1 to CP2: The rise and fall of Poseidon

This post follows Part 2: I see you, through cardboard chews & techno blues.

The snow was so severe that the Scout Centre in Hebden Hey (our usual CP1 venue) had been snowed-in. So the Spine hired the Birchcliffe Centre in Hebden Bridge as a last-minute replacement. It’s an imposing building; a stone mansion, fronted by a series of concave arches held aloft by Tuscan pillars. Inside its foyer, it felt like I’d entered an ancient place of worship. Then I was led through its mezzanine floor, down into the bosom of the great hall.

I was surrounded on three sides by wooden stands rising steeply toward lofty windows. A smattering of spectators gazed down toward me.

This felt more like a Colosseum, and I was in the arena. I imagined a lion being released, the audience goading it, and a brutal fight to the death.

It felt like an appropriate moment to make the first of my statements, this one originating from the global anti-poverty charity Oxfam:

That sobering business taken care of, I moved on to tackle my new-for-2025 laminated checkpoint checklist. Feeling many pairs of eyes boring into me from the stands, I tried my best to look like a competent professional while I worked through it.

I hit the ‘rest’ button on my Enduro 2, which inexplicably crashed. Then I hit the ‘rest’ button on my Forerunner 955, which also acted up, but after some perseverance it did eventually enter its rest mode. A minor success there.

Next, I couldn’t get either Garmin watch to charge. I’d prepared for this eventuality by bringing 5 USB-C cables and 10 Garmin adapters in my drop bag; but it seemed that none of them worked, which made no sense whatsoever.

After 5 minutes of frantic cable switching and heightening frustration, I flicked the Enduro 2 onto its settings screen so I could see the battery percentage. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted the number tick upwards by one percent. What…?

I threw my arms up in the air in disbelief. It turned out both my Garmin watches had been charging, they just hadn’t been showing their charging overlays like they usually do.

“F***ING GARMIN!” I muttered under my breath. Well, I’d certainly intended to mutter it under my breath; but the runners, volunteers and spectators all seemed to be staring at me. Perhaps I hadn’t muttered it, so much as bellowed it across the whole hall… after spending half a day battling the Enduro 2’s crashes and locational myopia, something had to give.

I moved onto charging my phone, but that turned out to be suffering from the most terrible of afflictions: a moist charging port. It took quite some perseverance to get that going.

With all the technical challenges keeping me occupied, I straight up forgot about the 12-24 hour deluge ahead. It slipped my mind to switch my lightweight waterproof jacket for my heavy-duty Phase Nano, and to replace my lightweight waterproof trousers with my rugged Montanes. While I switched to larger shoes, I forgot to fit them with gaiters. I accidentally left behind my hooded windproof. And as for the extra midlayer I’d intended to pack, that too become just another unfulfilled intention lost in the mists of technological despair.

In need of some good news, I fired up the Spine’s OpenTracking webpage to check my brother’s progress in Challenger South. I found him close to Gargrave, which was pretty good going for the heavy snow conditions, and bode well for his completing the race.

I was almost ready to go when I noticed my Enduro 2 hadn’t built up much charge. When I kept an eye on the charge percentage, I realised it’d actually stopped charging. There’d been no easy way to tell without its usual charging overlay. The f***ing thing!

That ended up delaying me for quite a while longer while I twiddled my thumbs waiting for it to charge back up. (Usually I’d have charged it on the go, but given all the trouble I was having with it today, I preferred to wait).

With the Enduro finally sufficiently recharged, I made to leave for the second time. I was pretty nonplussed to see I’d spent 90 minutes inside CP1, basically the same sluggish turnaround time as last year. But I took solace from the fact that most of it was due to Garmin malfunctions.

Thumbs Down To Colden

It was a long way back from the Birchcliffe Centre to the Pennine Way. Just like the runners from earlier, I too returned in silence, evading the eyelines of those still on their way to CP1.

A couple of them asked me how far it was. I smiled back and tried my best to meld honesty and encouragement into the phrase “it’s a little way yet, but it’s worth the wait”. What else could I say - “a few kilometres further, then drop down a near-vertical road, traipse along the river, through the town, dodge the raving drunkard, and climb up the other side of the valley?”

By the time I rejoined the Pennine Way, I calculated that this leg would be about 7km longer than usual, making it at least 106km! Rather a long way before I could resupply. Especially with deepening snow, another diversion ahead, and that weather forecast predicting a half day or so of rain...

First things first, I still had to get myself along the Pennine Way to Colden (where CP1 would usually be found), so I could properly begin the second leg. I needed to drop back down into the same valley I’d just clambered out of, then climb all the way up the other side, through a mix of Hebden’s cobbled pathways, narrow stone-walled alleys, fields and river crossings, until I reached Colden.

That was easier said than done in this snow.

With night setting in, the wind picking up and temperatures plummeting fast, I had to raise my hood and add my fleece-lined mitts. I’d have added more layers, but there was nowhere suitably sheltered to stop. The snow continued to deepen, and slippery ice cropped up ever more frequently, all contributing to my steadily slowing pace.

It was a tricky little climb away from the river. In the darkness, it wasn’t easy to spot the patch of black ice on the path. My Mafates’ Vibram Megagrip soles were my last line of defence, but they were no match for such a supremely slick surface. So my feet simply shot out from under me, and I came crashing down onto the ice. I softened my landing by outstretching an arm, which certainly benefited my hip, but not my thumb.

I writhed around on the ice, simultaneously trying to right myself and distract from the splitting pain in my hand. Try as I might, with just two legs and one hand functioning, I couldn’t get enough purchase on the ice to stand. So I sat myself up, and paused, taking stock. My thumb was injured, and it was too painful to remove the glove to take a look at it.

My headtorch was skew-whiff, so I righted that, and looked around for the energy bar I’d been eating. I found it wedged in the snow behind me. My waterproof mitts had been dangling by their cords at the time, so my gloves were soaked through and my hands were freezing. I needed to get my fleecy mitts on, but without a functioning left thumb that was really difficult. So I did the only thing I could, and gradually worked each mitt up over my gloves using my teeth.

Using the rocks by my side for balance, I managed after a few attempts to haul myself up and safely onto solid snow.

I’d injured a thumb last year too. But this time the injury was worse, and it was still very early on in the race, with most of the course ahead of me. How would I manage with only one functioning hand?

How far was it to Colden from here? I looked at my Enduro 2 for answers, but that thing still hadn’t managed to recalculate its waypoint distances since Hebden. I might as well have been carrying a chocolate teapot. At least I could’ve eaten that.

The Wrong Spikes

Between all the snow, and wind, and one immobile hand, it was nearly midnight by the time I reached Colden. I hadn’t been able to look after myself properly, so there was much to sort out here. Out of the wind, I delicately worked a windproof jacket over my immobile thumb, and removed some food from my pack.

I ate while hiking up over snowy cobblestones, and used the opportunity to run some calculations. Originally I’d estimated 22 hours for the CP1 → CP2 leg. Factoring in an extra 7km from the relocation of CP1, the worsening underfoot conditions, my broken hand, and the approaching weatherfront coupled with the bad weather gear that I’d forgotten to bring, that 22 hours was starting to look mightily optimistic. I just hoped I had enough food and power to make it to Hawes.

A sharp climb away from Heptonstall Moor brought me to a large glossy ice sheet. It angled down into a darkness my headtorch couldn’t illuminate. I rested a foot on it, intending to gauge its friction. But my foot slid straight away from under me, down toward the precipice. I lost my balance, though I just managed to launch my bodyweight from my other foot, angling my body away from that cliff edge. I came crashing down, landing half on that slick ice sheet; but fortunately, half on a layer of thick snow, which was just enough to halt my slide down into oblivion.

A near-death experience amply met my threshold for microspikes, so I hauled myself up into the snow to put on my Yaktrax. Feeling much more confident in these clunky contraptions, I bounded along quite happily - for all of 60 seconds, until the trail spat me out onto a tarmac road.

I sighed and stopped to take off the Yaktrax, spending a couple of minutes stuffing the awkward things back into the little black bag I’d brought for them. Not 20 seconds afterwards, my grip faltered again as more ice materialised on the road.

I glared at the bag with my Yaktrax. I couldn’t play yo-yo, taking them off and putting them back on every couple of minutes. They probably wouldn’t be much use on these razor thin layers of ice anyway. This needed nanospikes, and I didn’t have any of those.

It was with a heavy heart that I delicately picked my way up the slippery road. If I couldn’t make good progress through the deep snow, or the ice sheets, or now even the roads; then where, exactly, could I make good progress? How bloody long would it take to get to Hawes at this pace?

Why was I putting myself through this nonsense again?

Arctic Explorer

Reaching Walshaw Dean Reservoir brought memories flooding back from last year. I remembered standing right in this very spot, clasping my shoulder in agony, reckoning that my race was run, and wondering how I’d even make it to a place of safety in those freezing temperatures.

At least it wasn’t as cold this year, and there wasn’t nearly so much ice. My shoulder was alright too, even in spite of my sewing faux-pas. But the snow was deeper, my thumb was buggered, and my lack of a why was dragging me down. Why… why do this again?

Conditions deteriorated further over Top Withens, where the snow deepened to waist height. I was immensely grateful that the Challenger South runners had broken trail yesterday, leaving half-metre deep footprints and chasms. Even so, just to land my feet in those footprints, I had to raise my legs up to my chest with each step.

Then there was the curiosity of the thaw. It had begun, and was resulting in meltwater flowing beneath the snow. With every step I took, I could never be sure if the snow layers would hold, or whether they’d fail, and plummet me down to the ground beneath. I used poles to help mitigate the worst of it.

From Ponden Reservoir, the long climb over Bare Hill revealed how the fell had gained its name. Fully exposed up here for a long and arduous trudge through the deep snow, the wind howled something silly. And when the footprint chasms grew even deeper, they diverged from our charted GPX route, leaving me forging new paths in places and gambling with the off-GPX trodden route in others. It felt like a scene out of a movie where an Arctic explorer battles a storm in a fight for his very survival.

I breathed a sigh of relief when I recognised the hillside descent to Cowling. I remembered that it was in the little bus shelter down below that I’d stopped to add a jacket last year, and had frozen my hands in the process. I’d stop there again now, add more clothes and eat some food, because all that poling through the snow had left me ravenous.

But somehow I talked myself out of stopping at the bus shelter, and instead continued straight through the town of Cowling. Hungry and cold, the respite of Lothersdale while within 4km still felt an awfully long way away.

Freddy Krueger and the Face

I was descending a track dusted with a layer of snow just slight enough to obscure whatever was beneath it. So I never saw the ice that caused my body to swing acrobatically in three-dimensions. One minute I was a runner, and the next a passenger on a gravity-fuelled voyage of forces, vectors and motion.

My face made impact first, followed by the rest of my rag-doll body. I lay there, spread-eagled, with my face buried in the ice. What had just happened? I could feel pain, but couldn’t tell where from. Was my nose broken? No, I didn’t think so. If my nose was broken I’d know it. I’d nose it. Ha! Nose. What a funny word.

My thumb, the same thumb from earlier, that was firing a few neurons for sure. Throbbing violently, like Popeye’s arm after popping a can of spinach. But if I was mainly feeling my thumb, then my nose couldn’t be too bad, could it?

I hauled myself to my feet where I held myself in a bent-over pose with my hands on my knees. Where I just slid further down the ice until I lost my balance again and tumbled back over in slow motion. There ought to be a night vision camera here streaming live to YouTube, I thought. I’d be a hit!

If I’d been unable to remove my glove to inspect my thumb earlier, I certainly wouldn’t be able to remove it after this. So there really wasn’t anything else to do other than crack on.

The rest of the journey to Lothersdale was fairly fresh in my memory from October’s recce with my brother, which helped me calm my frayed nerves and build back into a steady rate of progress. However, I was a bit concerned my face might look like it’d undergone the Freddy Krueger treatment. This wasn’t just a question of vanity. Medics were on the lookout for head injuries, as concussion could call into question one’s fitness to proceed. But I had remained conscious throughout, and if I remembered correctly, that was usually the deciding factor.

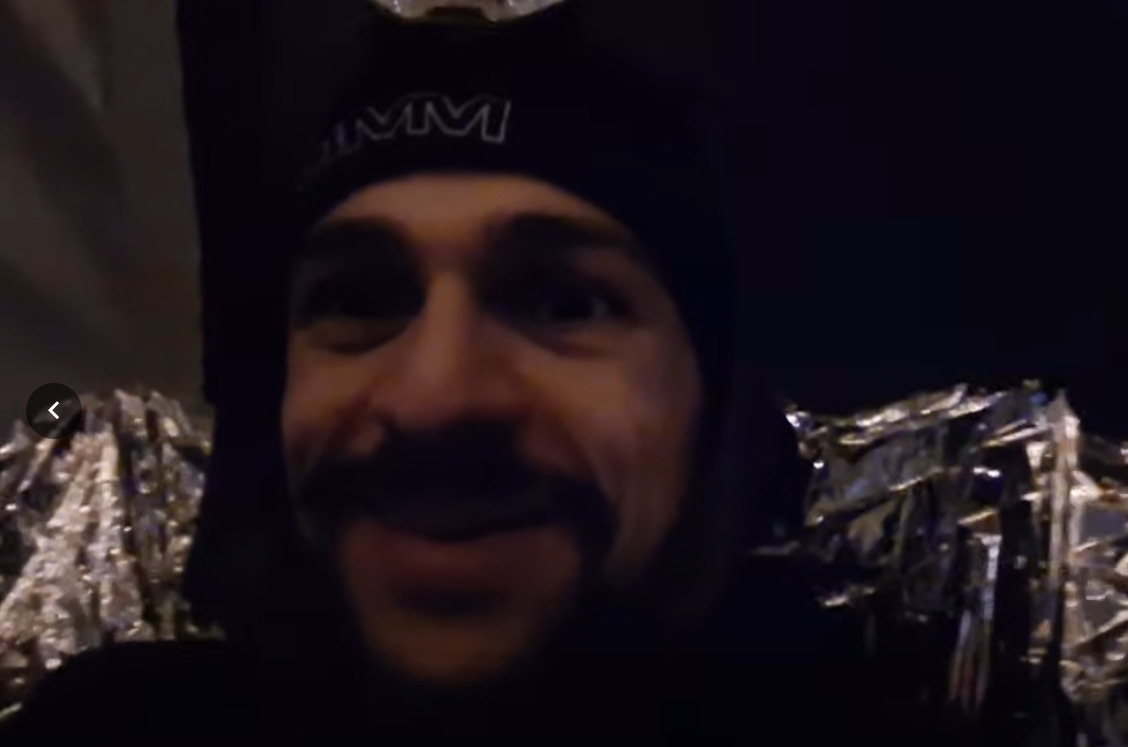

From last year, I knew exactly what to expect from the tri tent, and when I arrived I needed zero encouragement from the volunteers to burst inside, shout “Honey, I’m home!”, order a vegan butty and a tea, and collapse into a chair swaddled in a melange of warm blankets and heat reflectors.

This was a good, good place to be. I wolfed down my butty, downed my sugary tea, leant back and closed my eyes. Peace at last.

Time dripped through my fingers, far too quickly. Drip, drip, drip. It was pouring off of my throbbing thumb and pooling beneath me. We were only permitted to stay here for 30 minutes. Without a why to draw me back out into the winter wilderness, I intended to use every one of those 30.

I pulled out my phone to check on my brother’s progress in Challenger South. I was hugely relieved to learn he was almost at Horton. There was only another 20km or so to the finish at Hawes. He was going to complete it!

My 30 minutes was up, so I stuffed some money into a protesting MRT member’s hand and thanked them all profusely. This tent is such an important respite along the incredibly long drag to Gargrave.

Frank on Ice

Outside the tent, night had been busy turning back to day. The wind kicked in with some ferocity as soon as I climbed over rooftop height, so I was mightily grateful that my windproof did such a stellar job repelling the worst of it. I decided to stow my poles to help me focus on eating.

Under the slightly warmer daytime temperatures, I managed to maintain a fairly positive disposition, though a low point came when I watched a runner tackle a slippery ice patch by confidently sauntering over it without a care in the world, all while holding an animated conversation on his phone. How on earth did he do that? Over that same patch I slipped and slid and flailed around like a clown. Compared to the consummate professional in whose footsteps I was following, I must have looked like Frank out of Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em.

But the odd patch of ice aside, conditions really did seem to be improving now. Ahead, I could see a much flatter profile to the landscape. The fields were easier underfoot, with less snow and more green grass showing through. And my concern that snowmelt would turn the fields into muddy quagmires didn’t seem to be playing out, not this far south anyway.

On Cam Lane I picked up a drafter. His eyelids looked like they had 1 tonne anvils weighing them down, how he could see his way I didn’t know. He never spoke a word. I went through a cycle of holding gates open to let him catch up before pulling away from him again, but he always managed to stay within line of sight, and toiled hard to catch me back up before the next gate. I figured he was holding onto my coat-tails to save the hassle of navigating, and probably for some motivation too.

Since I’d started drinking caffeinated Tailwind after Lothersdale, my stomach hadn’t felt entirely settled, and I’d stopped eating. Now over the undulating fields toward Gargrave my chickens were coming home to roost, and it was I who was running low on energy. I slowed my pace to a run-walk, and after matching me for a while, my sleepwalking drafter decided to push on past me.

As I watched him disappear over the undulations, I scored a minor victory by finally managing to ease the glove off my injured hand. There weren’t any bones sticking through my palm, so that was a plus. Come on, mate. Gargrave isn’t far away. Shake a leg!

My arrival time into Gargrave provided a simple way to compare progress against last year. The Co-Op opens at 7am, and last year I’d arrived almost bang on 7am, in what could have been described as perfect timing. This year, I’d arrived at 10:20. I was three-and-a-quarter hours behind. I’d lost all that and more since CP1.

Sure, for a fairer comparison I ought to account for the 7+ kilometres of additional mileage from the diversion to the relocated CP1. But even that still left me an hour or so behind.

I plonked myself down on the bench seating in Gargrave’s semi-circular outdoor shelter, and carefully extracted my phone from its broken zip pocket to check on my brother’s progress. He was just 10km from the finish now. He basically had it in the bag!

Then I checked on Steve, my friend who was also running the full. He was on the approach to Lothersdale; so not all that far behind me, and about to enjoy a 30 minute break. Everyone was doing well! Everyone else, anyway. Goodness knows what I was up to.

Food-wise, I still had plenty of supplies remaining - in stark contrast to the first leg. But it still made sense to visit the Co-Op and scavenge some proper grub. There I found a jackfruit & rice bowl, a vegetable samosa, and a strawberry & banana smoothie, and carted the lot back to the outdoor shelter to feast.

In between mouthfuls, I checked the weather forecast, hoping the 12+ hours of rain might have faded away. But no, the forecast was upgraded to ‘heavy’ rain, and it was scheduled to run all the way from my arrival at Malham Tarn through the night and well into the following morning.

Since the rain was almost upon me, I used the opportunity to wrap myself up in my waterproofs. I really wished I’d brought my heavyweight gear with me, this ultra lightweight stuff wouldn’t last 5 minutes.

On the way out of Gargrave, while I was doing another Frank Spencer impression on an icy road, someone shouted my name. It was Mark Collinson, out walking his dog.

I’d run with Mark briefly during last year’s Spine. We’d met along the banks of the River Tees before CP3, during a torrential downpour that left us both soaked, shivering, and extremely appreciative of the crackling fire at Langdon Beck YHA.

After some reminiscing with Mark, I bid him farewell and trotted off, lost in memories of last year’s Spine. Glancing down at my Enduro 2, I was overjoyed to see it actually working for once, showing me the distance to the next checkpoint and everything!

But… wait a minute, where was my route line? I cocked an eyebrow and stared at the screen. Bugger, I was off course. I zoomed the screen out, and found I’d missed my turning a good half a km ago. And the Enduro 2 knew it, and hadn’t bothered notifying me…? This same watch had been perfect last year. What for the love of gadgetry was going on?!

The Valleys and Tarns of Yesteryear

Having righted my route, I soon found myself wending through a peaceful valley. The superb path meandered lazily around River Aire, neither hugging its banks nor veering too far from them.

I recalled this section well. Last year, I’d struggled badly with sleep demons here. I’d drifted in and out of consciousness, struggling to keep abreast of where real world ended and dreamscape began.

To see this section again, more compos mentis this time, felt meaningful. Also I felt relieved that it was mostly as I had remembered, despite my state of semi-consciousness at the time. Though I did find it curious how my memories were confined to the beauty of the valley itself, with no recollection of the resplendent fells to either side. Had I not looked up?

So why was I back here, pounding these trails again, I wondered? “I think part of it is reliving the trauma, revisiting the sites, and just making sense of what happened”.

I definitely felt a catharsis from this stretch of trail.

However, no section of the Spine leaves one entirely unchallenged. In the relative warmth of midday, with the valley protecting me from the wind and being wrapped up in not-very-breathable waterproofs, I actually found myself overheating.

So I removed my waterproofs, and then the rain clouds spat; so I re-added them, then the rain stopped and I removed them again, and so on and so forth, seemingly ad-infinitum. The ominous clouds seemed to take great pleasure in toying with me.

I breezed through Malham, acknowledging a couple of members of the Spine Safety Team, and turned my mind ahead toward Malham Cove. I relished the opportunity to return there, since I most fondly recalled the unbridled pleasure I’d taken from leaping over its organically-shaped boulders last year.

At the top of the climb to the Cove, a race photographer snapped photos and then pointed me in the direction he’d seen other runners head. Helpful, since navigating this boulder field is much easier said than done.

However, for some reason I felt I knew better, and made my way over the boulders. Just like last year, I went off in completely the wrong direction. And while I tried to extract myself from many tricky spots on treacherous snowed-in rocks, I imagined the photographer watching from afar, throwing his arms in the air, questioning how on earth this idiot had managed to get himself all the way up here from Edale.

After a much tougher boulder scramble than necessary, there was still a long slog to go over an awkward mix of rocks and tufty bogs to reach Malham Tarn, during which my feet were rarely out of water from all the snowmelt. My Dexshell waterproof socks had failed a long time ago, so in a practical sense the immersion hardly mattered, but it served as a reminder that I’d need to pay close attention to the state of my feet going forward.

Reaching Malham Tarn somehow felt like arriving back home. I kept staring across the dark waters of the lake, searching for the ‘mansion’ that I swore I’d seen from this vantage point last year. But try as I might, I couldn’t pick it out. It hadn’t been a hallucination though, since a kilometre out from the CP I finally spotted it on the approach.

I Should Never Have Re-entered

CP1.5 was located in one of the small outbuildings behind the mansion. I requested a tea and some hot water, in order to deploy one of my innovations for 2025: a dehydrated meal. That was a lesson I’d learned right here at Malham Tarn, from watching others tucking into their steaming hot meals, while I could only chew on a cold bar.

This time, I had a hot meal of my own, and my chipotle chilli with rice was delicious! I wolfed it down like a shipwrecked passenger might their first meal back on dry land. It was so good that I kicked myself for only packing a couple more dehydrated meals in my drop bag. What if there were more kettles than I had hot meals? If I found a kettle along the Pennine Way, I decided I wanted a meal to cook with it.

Before I left, I decided to give my feet the best chance to avoid trenchfoot by performing a full sock change. It was a gamble, given the next stretch was probably going to be boggy straight out the blocks and I only had a limited supply of Dexshells, but I calculated it was a gamble worth taking. “Use the good vanilla” - I couldn’t remember where I’d read that phrase, but that’s what I was doing. Using the good vanilla. (My Savage Trail friends will appreciate the sock-food metaphor, and if I’d had any Pasta alla Norma, I’d have certainly sprinkled that on too).

Amidst my refuelling and foot-culinary preparations, there was a sobering development in the checkpoint. Two chaps who I’d breakfasted with yesterday morning, Cedric and Ashley, were both here. They were both injured, and were both having to withdraw from the race.

I’d traded thoughts and places with Ashley on multiple occasions from Devil’s Dyke onwards, and had fully expected him to go on and perform well. And Cedric - I knew him from last year’s Spine, and knew what finishing meant to him this year.

They were both wishing me well, but I could see the sadness in their eyes, and hear a mix of dejection, frustration and longing in their voices. They’d have given their right arms to continue in the race. And that made me feel supremely awkward.

Because I’d already completed it. I didn’t seem to have any material reason I could put my finger on to run it again. I would happily have traded places with either of them then and there. I was taking a place from someone who needed the finish more than I. And, frankly, between my wafer-thin waterproofs and the torrential rain about to begin, this felt like an the ideal place to hang up my gear and duck out of the race.

I should never have re-entered.

“Make the most of it!” they insisted. It sounded as if they planning to live vicariously through me, as I had through my brother.

How could I possibly respond? If I’d told them I couldn’t have given a toss about the race; that I had no motivation, no why, and would much rather have quit, that’d have knocked the wind out of whatever sails they had left. But if I’d acted as though I were raring to go, that’d have been a brazen lie.

So I clammed up, unable to compose a suitable reply. In the end I diverted the conversation, wished them both a speedy recovery and hurried out of the CP with my tail between my legs.

Other people desperately wanted to run this while I desperately wanted not to. What on earth was I doing here? Taking up other people’s places, that’s what. I was an unwilling observer getting in everybody’s way.

I should never have re-entered.

Through the fading light, what had been a blue sky early in the day was now a mat of grubby cotton-wool. It grew dirtier, more ominous, and started to rain; light at first, but rapidly building into a deluge that had me soaked through in minutes. The darker and wetter things got, the angrier the scene became.

Yet there was someone else, or something else, out here on these embattled fells. A massive mechanical monster with an evil grin of high beams, tearing around the fellside like one of the Sentinels. Had a kid stolen a multimillion-pound tractor and taken it for a joyride in this f***ing storm? I needed this like a shot in the arm.

I should never have re-entered.

The Easy 10k to Horton

I couldn’t remember what was coming up ahead very clearly, but I figured the route would take me directly to Horton, and from there up-and-over Pen-y-Ghent to CP2 at Hawes. How long would I need to endure these conditions before I reached cover at Horton? In resigned hope, I looked at my Enduro 2, willing it to show me my waypoint distances; but of course, it was still as high as a kite, showing me simultaneously off- and on-course.

Never mind about the Enduro. Horton couldn’t be that far away, surely… 10k, perhaps?

I began my climb up Little Fell on a snowy, slushy, waterlogged trail. The higher I climbed, the more things deteriorated. Wind buffeted me from the side, and the rain ratcheted up until I may as well have been standing under a power shower. Underfoot, the slush was replaced by snow that grew deeper and deeper, until it overtopped my quads, forcing me to wade and then clown-walk through it.

The deep, deep footsteps left by the Challenger South runners made it so much easier than it would’ve been to break trail through this alien landscape, but the effort was still extremely weighty. Just lifting my legs high enough to clear the snow was a tall ask for a short chap like me, especially as I am most definitely not a yogi.

Bracing myself against the doof-doof of my foot falling through multiple collapsing layers of snow, down into the unknown abyss below, was both tiring and perilous in equal measure.

Then the footsteps and carved chasms began to deviate from the GPS course, like they had over Bare Fell. I investigated side routes that looked more accurate, only to find them veer further off course, or disappear entirely. I had to break fresh trails to get back to better paths, sometimes getting stuck in waist-deep snow I could hardly move through at all.

Meanwhile, the wind gusted, the rain poured, and fog set in. This bounced the light from my headtorch straight back into my face, blinding me rather than illuminating the way. It was another world up here.

I’d been fighting the fell and the weather for days, weeks, most probably decades. But finally, mercifully the angle of the terrain began to veer downwards. Over this side of the fell, sharp wet rocks peeked out of the snow, willing me to slip and impale myself. A cliff-edge emerged to my side, the pitch black beyond leaving no question as to the implications of a slip here. And the rocks by the edge were slippery, interspersed by deep snow whose behaviour was entirely unpredictable. Cautiously, I manoeuvred myself downwards, weighing a rapid descent out of the weather against the need to survive the scramble.

When the rocky terrain eased, the mud & ice began. Rain fired into my face like darts of ice, causing me to draw in my hood, though that offered scant protection. I just wanted to get down, and so I threw caution to the wind and hurled myself down the fellside, landing my feet as quickly as I dared such that they may catch me when I slipped.

But the ice darts were softening, and the wind was relenting, and quite possibly, the ground was gradually levelling out. I didn’t know it at the time, but I’d just overtopped Fountain’s Fell.

The trail popped me out onto Silverdale Road, into relative calm and quiet. There was only a light smattering of rain now. I stood for a moment, in awe of what I’d just experienced. The raw forces of nature, the extraterrestrial world, and the claustrophobic bubble of solitary confinement.

Gazing back in the direction of the fell, I spotted a headlight appear high up above, and gradually edge fractionally closer. I couldn’t believe it. That was the first sign of life I’d seen for hours.

I snapped back to the moment. I must be nearly at Horton now, which was probably just down the road, and thank goodness for that! After hours of freezing wet-through conditions, and hardly eating or drinking a thing, I desperately needed a place to recover.

My Enduro 2 still wasn’t showing any waypoint distances, so I zoomed around its map, trying to locate Horton and estimate its distance. This wasn’t easy on the Enduro’s little screen, but one thing became clear - it was bloody miles away.

F*** this for a game of toy soldiers. I invested a couple of minutes rolling up each of the four tight-fitting sleeves on my left arm to reveal my trusty Forerunner 955, and opened up its nav screen. See, this Garmin watch was working - why couldn’t the so-called Enduro 2 manage it? The clue’s in the name - Enduro - that’s literally the whole point of the bloody thing. Anyway, there it was, Horton. Just 9km away.

Huh - 9km? I played with it on my tongue. 9, nine, n-iii-ne. Such a funny word, n-iii-ne.

“How are there still NINE KILOMETRES to Horton?” I shouted in the direction of the speck of light descending towards me. “There were 9 kilometres to Horton 3 f***ing hours ago when I left Malham bloody Tarn!” At least, I had thought there were. Assumed there were.

“That f***ing Enduro 2! Why the f*** can’t it f***ing work for more than a f***ing minute at a f***ing time, that crash-looping waypoint-blind non-charging piece of sh**!”

The Pen-Y-Ghent Conundrum

I was growing cold, standing in the rain in my sodden clothes. And that headtorch was drawing closer, perhaps a couple of minutes away. Not fancying company at this precise moment, I turned away and set off along the road.

The road was flooded, and iced, of course. I picked my way around obstacles at a snail’s pace, no longer caring much at all. The runner from behind caught me up, though we didn’t exchange words. He didn’t appear very happy either.

I was going to let him go, but at the last minute decided to tag along behind him instead. Why not? Might as well, the faster I moved the sooner I’d reach Horton. But I soon found I didn’t want to run in his wake, and so I overtook him instead, seeking solitude up ahead.

A bright sign stopped me in my tracks. It was an arrow, pointing left. A diversion arrow?

I racked my brains. I knew there was a diversion, but that was around Pen-y-Ghent, and I thought Pen-y-Ghent came after Horton. Had I somehow missed Horton? Surely not.

The anonymous runner caught me back up, along with another runner who had his arm outstretched, holding a handheld GPS. This was the diversion, they both agreed, and set off in the direction of the sign.

I remained by the sign, still confused. If the diversion was left, then I had to be standing at the base of Pen-y-Ghent. So Pen-y-Ghent came before Horton, and I must have misremembered the route. Really? Argh, f*** it...

Still not entirely convinced, I extracted my Garmin eTrex handheld GPS from the depths of my pack. I’d loaded all the diversion routes onto it. But no sooner had I pressed the power button, I realised I didn’t have the patience to wait 5-10 minutes for this old Garmin device to boot up and, if I was lucky, deign to show me a map. I shoved the thing back in my pack, and shot off to catch up with the other two runners. F*** Garmin, I’d be better off following them.

The diversion started at 530m at the base of Pen-y-Ghent’s southern ascent, and forked us west down a direct 300m descent emerging in Horton in Ribblesdale.

Just like the descent from Fountain’s Fell, the rain continued unabated, the fog played unsporting games with the light from our headtorches, and in the deep snow, this technical, scrambly descent was borderline treacherous. We three kept our heads down and rotated the lead runner like a peloton, all the while pushing each other to move faster and faster over the terrain, regardless of the snow, the ice, the sheer drops; for we each needed to reach shelter.

Safely down in Horton, I pushed the pace even harder on the roads, dropping the other two until finally - finally - I reached the waypoint that I’d been searching for for the past 4 hours and 20 minutes. Horton’s public toilets.

In a moment of madness, I shrugged, said “f*** it”, and ran past, setting my sights on Hawes. But thank goodness I had enough sense remaining to re-evaluate; to stop, turn around, and retrace my steps back to the toilet block. I hit the rest button to track my rest time, which naturally crashed the Enduro 2.

Inside were my two sullen compatriots. The chap in the thick orange storm-proof waterproofs was Leif Abrahamsen, a Norwegian who was only running Winter Spine as a kit test before Arctic Spine in February (a race nobody had ever finished before, which he would go on to win). Leif looked relatively unflustered compared to us two, but I think it’s fair to say we’d all been through something out there.

With the dripping of our clothes, expansive puddles were emerging on the floor. I set some of my devices on charge, and then set about replacing my baselayers with my dry spares. Every item that went back on over that dry layer I could have wrung a puddle of water out of.

Before I left, I took a distance read off of my functioning Forerunner 955. There was just over 22km to go to Hawes. I couldn’t remember what the route entailed though... Pen-y-Ghent was obviously behind me now, so I just hoped it’d be flat and easy to Hawes.

The Battle with Poseidon

I set off in the lead, looking to put some distance between us. It was nothing against the other two runners at all; their company had been a great help on the scrambly descent, but I just wanted time alone to reflect on that last stretch from Malham Tarn.

The long, gradual, rainy climb through snow played right into my hands here. Its continual effortful awkwardness afforded me the perfect opportunity to take stock and place the last few hours into a wider context. And as I did, I began to stop fighting the rain, but rather accept and embrace it.

Both the rain and snowmelt fed into the rivers continually snaking across my path. Some had developed deep chasms of aggressive, fast-moving torrents that would have been quite dangerous to ford. It took some persistence and creative thinking to locate sequences of tufts, reeds and islands that I could string together into paths across, which was initially quite a fun, creative thought process.

Despite my success at building back some positivity, I was again falling back into a downward spiral. I’d started coughing incessantly, just like my compatriots had been back at Horton. Now my throat was growing sore, and I was starting to feel genuinely ill. Had I picked something up from them?

Or was it dehydration? I took a sip of my Tailwind, and was surprised to find I couldn’t stand it. Why? I’d drunk very little in the past 5-6 hours. My mind rattled through the contents of Tailwind, and stopped at salt. It must be the salt I was rejecting. I realised I was seriously dehydrated.

For some reason I hadn’t refilled my water in Horton. A quick assessment revealed that, excluding the Tailwind, I only had a few sips left. So I was badly dehydrated and basically out of water, with no idea of what lay ahead of me.

All things considered, of all the race mismanagements I’d ever orchestrated in my career, the last 12 hours felt like one of the worst. Not the worst; that dubious honour was reserved for my Cockbain Track 100 fiasco, a true masterclass in bumbling idiocy. But this was up there. The waterproofs. The nutrition and hydration. Misremembering the route. Technology failures. Then, not refilling water - what had I been thinking? Had that preposterous “observer” mindset been affecting my decisionmaking process?

I should probably turn back, return to Horton. Drink water. Sort myself out, regroup, and go again.

But that admission of defeat hit me like a blow to the stomach. I was not going to let a duff Garmin wristwatch derail me. I was a bloody ultrarunner. I’d sort myself out. Somehow...

I just needed water. Water. If only I could find some water.

I looked intently around me, determined to find an answer to my dehydration puzzle; but alas, there was nothing.

“Sh**”, I exclaimed, as I unexpectedly dropped down into a river of snowmelt. I hadn’t been paying attention to where I was going. I stared down at my swimming feet, nonplussed. Then adjusted my gaze back to the sea of white all around me. Then up further, toward another river that I could hear gushing ahead.

Everything I could see. Everything I could hear. Snow. Rivers. Meltwater. Rain.

It’s all f***ing water!

Within seconds, I had a filter flask filled to the brim and was downing delicious, pure, salt-free water. I necked a litre then and there. Just like that, all my cognitive functions whirred back up. I took electrolytes, and plenty more water. Now I felt much better. There was a feeling of embarrassment that I’d let myself get so badly dehydrated while hardly being able to move for water, but at least I’d sorted it out in the end.

Climbing into Hell

Hours passed into the night and the climb grew no easier. Which towering mountain was this, for goodness sake? To deal with the cold, the building wind and the unrelenting rain, I put on all the clothes I had, down to my balaclava, buffs, and for the first time ever, a pair of disposable handwarmers (which certainly wasn’t very green of me).

While I was initially unimpressed by the limited effect of the handwarmers, I soon came to appreciate their subtle warmth. But my waterproof mitts were completely soaked, and it wasn’t long before this penetrated into the handwarmers, degrading their performance until they became nothing more than heavy bags of cold water flapping around inside my mitts.

It was only when the trail merged onto track (Cam High Road - a notorious stretch of climb almost universally hated by participants) that hazy memories of this stretch to Hawes started coming back to me. Yes… I’d pushed this one right to the back of my memory, hadn’t I. Repressed it. Had dreams about it. Nightmares. I hadn’t been sure if they were real or imagined.

Last year, the weather had been offensively awful, the cold indescribable, and the underfoot conditions preposterous, amidst an alien landscape that felt as remote as anything I’d ever encountered. It mightn’t be quite so cold tonight, but the prospect of reliving aspects of that experience didn’t thrill me.

I should never have re-entered.

Still with no waypoints to go by on my Enduro 2, and unwilling to zoom around its map for fear of prompting another crash, I kept climbing and climbing and hoping the summit would emerge at the extent of my headlight beam. “This must be it”, I kept thinking to myself. It already felt like I’d been climbing up this fell for days.

Now I remembered - I’d come to a left hand turn. An exposed track with a stone wall to the side. Wind. Lots and lots of wind. Freezing cold. There’d be snow, ice. Lots of it. It’d been bad, really bad.

It was at that moment of recollection that I misjudged a patch of ice on the track ahead. My body rotated, I lost my legs to one side, and my upper body came crashing down; saved only by my left hand’s trusty, reliable, self-sacrificing thumb.

There was far more pain than either of the previous two falls, so I knew I’d done something quite notable. But up here in these conditions, what could one do?

Between the resounding pain in my hand, the building cold, this never-ending climb to the heavens, my lack of situational awareness thanks to the Enduro 2, and the cumulative effects of 40 hours of running, pressures on me were mounting.

I raised an eyebrow at the photographer to the right of the track. Well; not a photographer, actually, but their complete photographic setup. Lightbox, camera stands, the works. Funny, really, that they’d have all that expensive gear setup here, in the middle of the night, in these extreme conditions.

I paused to observe it all, and smiled a wry smile. It wasn’t real. But; I was curious, and so I hiked off the track and down the fellside toward it. Just before I could touch the first lightbox, everything in front of my eyes disappeared. I knew it would, because it wasn’t there. I’d been through all this last year.

Why was I doing this again? I’d probably broken my hand, and I was dug into snow on the side of a high fell in negative whatever Celsius trying to touch an imaginary photography studio.

As if standing in solidarity with my situation, my Enduro 2 chose this moment to restore its waypoint functionality. And just like that, voila - I had situational context again.

Seeing the distance to Hawes triggered more memories from last year. This stretch must be Cam High Road. Various numbers stood out in my memory: 9, 8, 6, 4… there was something significant about each of these numbers. No doubt distances to CP2, each with a notable feature on the ground. I thought 9km might be the left hand turn at the summit, before that nightmarish exposed stretch.

So 9km became my target. And, indeed, as the waypoint distance ticked down to 9, the ground levelled off, and a track emerged to my left. Now I was getting somewhere.

That flat track deteriorated into deep snow that was hardly passable, so I hacked up onto the snowy banks to the right, where I found numerous trails of footprints meandering along these craggy banks. Here the wind howled something silly, and though one of my shoelaces came undone, this was not the place to pause and retie it.

My race number, which had been making one heck of a racket in the wind, broke free of its safety pins to be whisked high up into the sky, where it picked up a main wind and rocketed out of sight in a flash.

I kept dipping back down to the snowed-over track, vaguely recalling that I’d need to wind up on it eventually; but each time I returned to it I found it entirely impassable, and had to retreat back up onto the banks.

That point came at 6km, where the route veered off over felltop moorland. This had a bit of everything: bog, snow, ice, rocks. The bogs proved quite unpredictable. One caught me out wherein I disappeared up to my waist. Thereafter, I strongly suspected my bog-dunked voice recorder was only flashing its LED out of politeness, but was internally quite broken.

It was so exposed in the wind that with only one working hand, all I could do was plough onwards. It wasn’t until 1:30am that I found some overhanging ground that offered some shelter from the wind (though not the rain), where I could pause to eat and give my almost-dead Forerunner 955 a little boost of charge.

Bog Off, Box

I thought I remembered the descent to Hawes being a sharp, steep rocky downscramble. That never materialised. There was just a relatively gradual descent through mud and bog. It wasn’t long before I popped out of it into the familiar town of Hawes, where I felt totally confused.

It’d been an Odyssean quest to summit that fell. It’d taken hours, days, decades to complete; how could that little descent have returned me so much as quarter of the way back to ground level? There had to be more descending to come. There just had to be.

But apparently there wasn’t, for I was literally in Hawes. From here, the short run to the YHA was as bewildering for me as it was nostalgic. In some respects it felt victorious. I’d been put through the proverbial ringer today, and I’d more than prevailed - I’d turned Poseidon’s wrath into an elixir to restore my own strength.

At least, that’s the idea I tried to sell to myself as I limped my beleaguered body into the YHA. But it was my steamrollered mind, my sodden gear, and my broken thumb that told a truer story.

I wasn’t just an observer any more.

I was back down in the bowels of Zion, waging war against the Sentinels.

Battered and broken. Low on morale. Verging on defeat.

Why was I putting myself through this again - for that mystery box, right? That, and some bulls*** about a monkey?

You can’t be f***ing serious…

I should never have re-entered.

Continue reading Part 4: